But from where does this come, this

joyousness, this blithe spirit? It has to be rooted

in Radhakrishnan himself. Whatever the source of his

inspiration, without this childlike quality within him,

his sculptures could not soar. The stodginess of the

‘grown up' human being would hold back the free

spirit. That he has been able to hold on to this innocence

of the child, is in itself, a feat to be commended.

To transform that into his work is a gift that we wonder

at, and are able to enjoy at the same time.

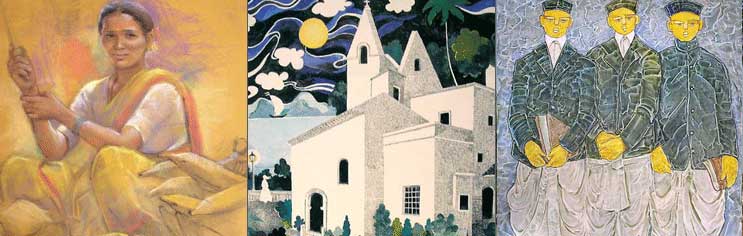

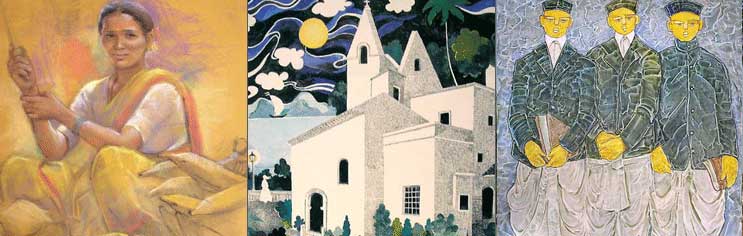

To try and categorise Radhakrishnan's work would be

insulting. To attempt to encapsulate talent or genius

is to limit the man and his work. But we must look back

(and forward) to Masui and Maiya. Masui, a Santhal boy

who was a model for Radhakrishnan in Santineketan, has

mutated from his human form, lithe, long limbed, smiling,

into an idea, a spark to ignite inspiration. He has

changed in everyway, except in his lightness of body

and of spirit. It is only fitting that Radhakrishnan

created for him a Maiya, female, young, oozing a sexuality

that she seems not aware of, or, if she is aware, then

not bound by it. Instead she complements Masui as much

as she is his opposite. Together they are complete,

a whole Universe, in their ability to be gods or children,

or both, for isn't there a purity in both.

Then there are his boxes, and his ramps. Both have

moved away from the individual into a portrayal of the

world. In his boxes he talks of migration into new cities,

new worlds, struggle, an ant-hill of humans with their

hopes and failures, their clinging on and falling off.

Each separate figure in a child's moulding, each completed

piece a work of art, sophisticated in thought as well

as in its interpretation.

The ramp portrays a Saint, a Rishi, Buddha, still immutable

and around him a pygmy world at his feet, continuing

with its daily tasks. Or is it a pygmy world dancing

the dance of life, worshipful and profane, like all

of us.

Like a yogi levitating, there is Radhakrishnan and

his work. Freeing himself of his earthly base materials,

he is stretching his imagination into new heights, different

directions, and following them there, is his expertise

with his material. And yet, in the necessary business

of linking his mind with his hand, of portraying what

his mind's eye sees, he is paradoxically doing the opposite

of Alchemy – turning an idea into metal.

back |