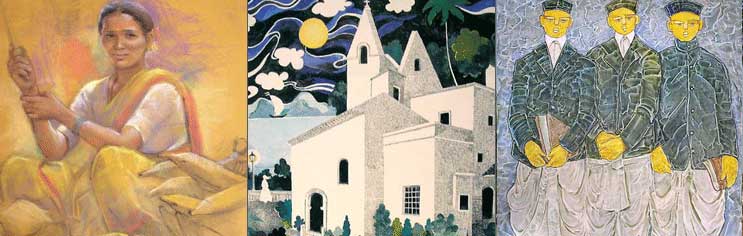

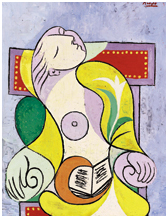

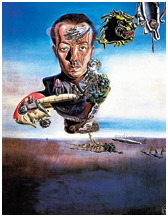

Pablo Picasso’s La Lecture (top) sold for £25.2 million and Salvador Dali’s Portrait de Paul Eluard for £13.5 million at Sotheby’s (London) recently. With the waiver, a gallery owner can now hope to save around Rs 26.7 crore while bringing the Picasso to India and Rs 14.3 crore on the Dali |

The Telegraph,Calcutta

The budget abolishes duty on import of artwork, but.... Somak Ghoshal paints the true picture

Days after the Government College of Art & Craft in Calcutta organised an exhibition of “fake” Tagores in February this year, the Union finance ministry made a significant concession in its annual budget, something that is likely to have a positive impact on the art scene in India.

The ministry abolished basic as well as additional customs duty on the import of certain kinds of artwork and antiquities into the country. This was one of the key recommendations made by the Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce and Industry (Ficci) in a report on the Indian art industry published last year. But, while Ficci had suggested the exemption of customs duty on the import of all types of artwork, the government has granted only a part of that wish.

Prior to this year’s budget, only the import of artwork meant to be shown in a public museum or national institution was exempted from customs duty. If the same were to be displayed in an art gallery, a customs duty was imposed at 14.71 per cent. Such exorbitant rates of taxation naturally did not encourage the entry of art into the country. Now, finally, the exemption of duties has been extended to art galleries as well — although strictly for the import of arts and antiquities that will be exhibited for non-commercial purposes only. So buyers and sellers of art do not really benefit from the bargain as they have to continue paying customs duty.

Predictably, the response from the art community is enthusiastic though tinged with scepticism. Those in the business of art are happy with the principle of this policy change as well as the possibilities it gives rise to. But then, they also realise that the government’s move does not really open up art — in the way liberalisation opened up the Indian economy in the 1990s — or help turn it into a viable commercial proposition.

“This is really unfortunate,” says Rakhi Sarkar, the chairperson of Ficci Committee on Art & Business of Art. “The government seems reluctant to offer incentives that can transform an informal sector like art into a vibrant business option.” Such a change, Sarkar believes, is waiting to happen in a “cultural destination” like India where the potential for “cultural commerce” is virtually unlimited.

To which, Neha Kirpal, the founding director of the India Art Summit, assents: “As organisers of an art fair in which over half of our clients come from abroad, we feel this development will make India one of the most significantly growing art destinations in the coming decade.”

Prateek Raja, one of the directors of Experimenter, an upcoming gallery in Calcutta, is also excited by the prospect of now being “able to showcase the very best art in India without having to pay customs duty”. But he admits that for commercial galleries there is “really no benefit from the sales point of view”.

Sarkar adds that in a globalised era, such irrationalities in the tax structure “only act as impediments that do not allow the sector to grow”. It is also patently unfair to impose absurd duties on individuals interested in buying great works of art. “After all, a Picasso bought by an Indian individual or an institution is also going to be an asset for the entire country,” she explains.

Three Studies for a Portrait of Lucian Freud by Francis Bacon, sold for £23m, can be imported for Rs 24.4cr less |

Raja agrees. “Indians are becoming more mindful of their cultural heritage, and global Indians now have the economic power to buy back objects of historical importance from abroad,” he says. “Even if antiquities are bought back by private collectors in India, there should be no duty on them once they are brought home.” As for contemporary art, Raja thinks that “a tax holiday for a few years would give a huge impetus to the sector”.

What took the government so long to remove customs duty, and that too, selectively? And why keep these anomalies in the tax structure when most other countries have done away with such archaic revenues?

“The government makes significant concessions in the tax regime only when there is a felt need that is articulated properly,” says Jawhar Sircar, the culture secretary. “The provision for the abolition of duties was there in customs laws for quite some time and was actually implemented in the case of the Kiran Nadar Museum of Modern Art (in Delhi) with the assistance of the ministry of culture.”

Sircar is more cautious about the extension of this privilege to art imported for commercial reasons. “Our purpose is to encourage the non-government sector — that is, corporate philanthropic organisations — to play a more active role in setting up museums and galleries. This duty concession is meant as a gesture of support by the government to them.” In any case, turning art into a “business option” is not “our prime driver”, he adds. “Greater involvement of the corporate and philanthropic sector in our art and museum scene is what we are looking for at this stage.”

Even within the current tax structure, there are far too many irregularities at the selling point. For instance, apart from value-added taxes, there are entry taxes and octroi in certain states. The system could be made simpler and more transparent by imposing a flat rate across all states.

“The government could also consider giving tax benefits to buyers of art. A slab exemption to individual and corporate collectors for new acquisitions every year will give a huge boost to the industry,” says Raja.

However, for sustained growth, the Indian art industry needs more comprehensive policies than just financial imperatives.

“At a fundamental level, the government should invest in infrastructure and education in the arts as well as in art management,” Kirpal says. “The aim should be to provide world-class training to Indian professionals and help develop talent.”

To this end, the ministry of culture has set up a committee, on Ficci’s advice, to promote and protect the interests of the various stakeholders in the Indian art industry.

But the government’s vision, at the moment, “is mainly sectoral”, says Sircar, focusing separately on the conservation and restoration of archives, library, museums, arts and antiquities.

But preservation and rejuvenation of the arts make little sense in a context that is yet to imbibe best practices of transparency, transaction and authentication.

As Sircar says, “Arts certification, the system by which fakes are detected and genuine artwork hallmarked, has been under discussion for several years now. We are hopeful that art experts will work out a mechanism for doing this. We cannot work on ad hoc interests every time a major fake excites attention.”

A year before the outbreak of the “fake” Tagores, Ficci had precisely recommended the setting up of region-wise authentication cells, based on a PPP model. These bodies could then, Ficci had suggested, “also cater to law enforcement agencies and courts as experts on record throughout the country”. Nothing has come of this suggestion as yet.

In the absence of a fool-proof system, the removal of import duty may backfire in a perverse way. If today we have a handful of fake Tagores to deal with, tomorrow there may be a dozen Picassos on display. |