“There are people who are coming who are saying: ‘I have money in my bag. Where do I start?’ ” Ms. Kirpal said.

She was only half joking. Just as the prolonged economic boom in China has contributed to globalized tastes and a major art scene in recent decades, India is now experiencing its own, relatively modest version of that phenomenon. At the Art Summit, the largest event of its kind in the country, many newly moneyed visitors were clearly curious about their options. Wealth managers turned up at panel discussions led by curators and college professors; a Kolkata businessman listened as a dealer patiently explained the French influence in the work S. H. Raza, a prominent Indian artist long based in Paris.

But they were also buying, across a wide spectrum of prices. One gallery owner from Mumbai said she was somewhat unprepared for what happened on preview day, before the fair opened to the public, when all three editions of a $13,000 neon light-and-acrylic piece by Tejal Shah, a young Mumbai artist, were snapped up by buyers. A New Delhi gallery sold 10 contemporary pieces, including photographs, paintings and sculpture, at prices ranging from $7,700 to $270,000.

Other dealers reported sales of contemporary Indian works for as much as $400,000. And two sold paintings by Picasso, each of which went for more than $1 million.

“In the hierarchy of needs, people are at a place now where they want to aesthetically satisfy themselves,” Ms. Kirpal said.

One of the most aggressive buyers in India in recent years has been Kiran Nadar, the wife of the billionaire technology baron Shiv Nadar and the founder of the unabashedly named Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, which opened on the eve of the Art Summit inside a new shopping mall a few miles away.

Ms. Nadar, who was a competitive bridge player long before she became an art collector, seems to have brought some of the same energy to acquiring art. She has built her collection swiftly and aggressively, turning up at international art auctions and buying several important examples of modern and contemporary Indian work.

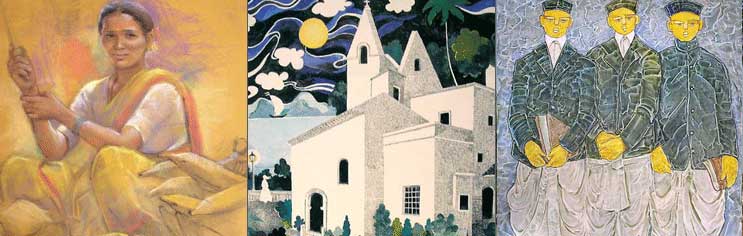

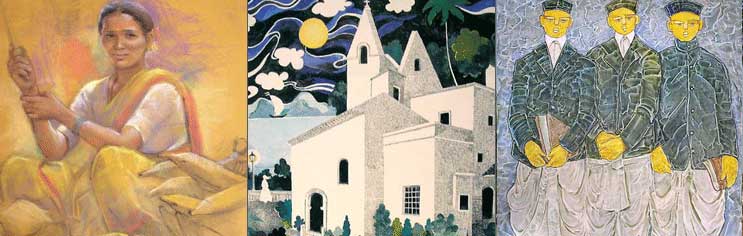

At her museum she is showing major pieces like a haunting three-panel green-and-ivory canvas called “Mahishasura” by the painter Tyeb Mehta, who died in 2009 and was associated with the influential Bombay Progressive Artists’ Group of the 1940s; a set of nudes by one of that group’s founders, F. N. Souza; a room-size steel-and-muslin mobile by Ranjani Shettar, a young Bangalore artist who shows widely in Europe and the United States as well as India; and a mammoth elephant by Bharati Kher of New Delhi, another internationally known artist, covered in her signature bindis.

Ms. Nadar’s most famous acquisition came last year: a large square canvas of geometric reds and oranges, called “Saurashtra,” by Mr. Raza, which she bought for nearly $3.5 million at a Christie’s auction, setting a record for Indian modern art. The piece takes up one wall at the top of her museum’s main exhibition hall.

It’s the kind of collection one might expect at a national art museum, except that in India government museums — in addition to being woefully neglected — rarely collect new work. Ms. Nadar is one of a number of the new private collectors who are trying to make up for that deficiency with museums of their own.

At least two other private museums are in the planning stages, one in Coimbatore, the other in eastern Kolkata. And there is already one devoted to new, often unknown contemporary work from across South Asia, called Devi Art Foundation, in the New Delhi suburb Gurgaon, which reflects the interests of its backers, the mother-and-son duo Lekha and Anupam Poddar, scions of one of India’s most established business families.

For her part Ms. Nadar sees investment in art among the newly rich as a civic good and does what she can to encourage it. “It can improve your aesthetics and be something you can bank on,” is one bottom-line argument she offers. “It’s like jewelry.”

The vogue for art buying was strong enough by this year’s Art Summit to attract galleries from 19 countries outside India, and the expanded fair also drew representatives from a handful of foreign museums like the Tate Modern, interested at the very least in the “spectacle and schmoozathon,” as one local dealer put it.

And in a scene reminiscent of “satellite” events held around more established art fairs, Feroze Gujral, a well-known socialite, invited four artists to put up an installation in a gutted villa that her family had acquired in the city’s most exclusive neighborhood. Then she staged a party.

Still, the summit faced its share of typically Indian challenges. One dealer kept a worried eye on a tangle of electrical cables buried under the carpet. Ms. Kirpal had to get the 10 domes of the exhibition hall covered with waterproof sheeting at the last minute. And thugs threatened the exhibition of India’s most famous painter, M.F. Husain; the Hindu right has for years railed against Mr. Husain for his representations of Hindu goddesses in the nude. Ms. Kirpal agreed to put up his works, then, fearing attacks, ordered them taken down, but was again persuaded to let them be mounted. By then Mr. Husain’s defenders had publicly criticized fair organizers.

Among those who came to view Mr. Husain’s paintings was India’s most powerful politician, Sonia Gandhi, head of the ruling Congress Party, and her visit too proved a headache. Inconveniently for the art-viewing public, she came toward the end of the last day of the fair. The police closed the gates, effectively shutting down the fair earlier than scheduled, leaving dealers and would-be Art Summit visitors angry.

And Mr. Husain himself did not attend. Out of fear, he lives in self-imposed exile in Dubai and London.