| |

THE adaptive process of Christianity and its assimilative tolerance was derived from the matrix of Hinduism, which, in turn, had modified its Aryanism by assimilation of pre-Aryan practices and deities, notably Shiva and his vehicle, the bull. The tradition of the artisan and craftsman remained Hindu and even when he became a Christian, and a forcibly converted Christian, it was he who gave his imprint and personality, and his features to Christ, St. Francis Xavier and other Catholic saints that crown Catholic Churches and shrines in Goa. Souza is firmly in this tradition, not least because he belongs to Bardez, a district that was Christianised, as will be detailed later, by the Franciscans. THE adaptive process of Christianity and its assimilative tolerance was derived from the matrix of Hinduism, which, in turn, had modified its Aryanism by assimilation of pre-Aryan practices and deities, notably Shiva and his vehicle, the bull. The tradition of the artisan and craftsman remained Hindu and even when he became a Christian, and a forcibly converted Christian, it was he who gave his imprint and personality, and his features to Christ, St. Francis Xavier and other Catholic saints that crown Catholic Churches and shrines in Goa. Souza is firmly in this tradition, not least because he belongs to Bardez, a district that was Christianised, as will be detailed later, by the Franciscans.

Knowledge of Portuguese was made compulsory and the language of the people, Konkani, was banned from the school curriculum. They could not erase it, though, from the tongues of people. The language has been imbued with vitality and humour because along with religion and this may be either Catholicism, or Hinduism, it is the bedrock of the life of village communities and these are the backbone of the Goan way of life. The Goans, an extremely articulate, hospitable and open-hearted community, have enriched Konkani by adopting and naturalising words from Portuguese, English, Kannada and Marathi. Although the State did not amend its laws and Konkani schools were only introduced in 1961 after Liberation, missionaries found themselves compelled to adopt Konkani, and indeed to teach it, in order to reach out to people. Eventually the only institution that helped in the enrichment of the language for the Catholics, at any rate, was the Church. The Goans joined seminaries in large numbers and through their sermons, hymns and primary education centres run by the church, institutionalised the use of Konkani, which is Souza's mother tongue. The fact that he speaks no Portuguese and that his father was the headmaster of an English school illustrates important distinctions within the Catholic community in Goa.

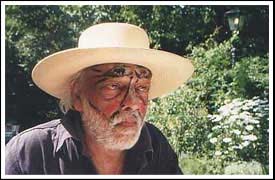

Souza was born in Saligco and in the "Konkankyana", a poem written in the 18th Century, the village is called Salgun situated in the Bardez district, an area christianised by the Franciscans. The various orders, the Dominicans, Jesuits, Fransciscan, and Augustinian among them, evangelised different sections of Goa and there is a marked difference between say, the Catholics of Bardez and those of Salcete, the district where Maria Souza, the artist's first wife, was born, which was Jesuit territory. Maria was born in Margco, in a street of palatial houses, elegant living, a rigid caste system underlying a rigorous Catholic belief. That the Jesuits did a thorough job of conversion is illustrated by the fact that the people of Salcete are the most evidently intense in their adherence to an inherited European cultural influence.

Just as in his iconography, Souza harks back to a pre-colonial history of Indian Christianity when Thomas, the Apostle, travelled along the Malabar coast to Kerala and beyond after pausing in Goa. His vision of the seafaring exploits of the Goan is expressed, as in "Arab Dhows in Goa" (1944), in terms of an identity shaped by its ancient position in Indian history as the centre of the spice trade with graceful Arab dhows gliding across the seas and a thriving economic and cultural link in existence much before colonial enterprises disrupted a natural cultural development. The artist has been both nurtured and tortured by his divided sensibility, his forked tongue, his inarticulate rage which found statement both in vibrant colour and in evocative prose: "I myself read, write and think in a language alien to me: English, a language not my mother tongue but spoken to me by my mother since my childhood. But the difficulty arose from the very start to express myself. For how can one articulate in Anglo-Saxon with a jewelled mandible that was fashioned by the ancient Konkan goldsmiths of Goa? It bewilders me to think that my inarticulation was due to England having possessed a lot of boats, which had netted India into its vast Empire."

Souza, the name, is to be explained not as descendant of the Portuguese, but as one whose ancestors were, by coercion, for reasons of faith or tempted by economic benefits, converted by the Portuguese. The act of baptism requires godfathers, and these were drawn from officiating priests or from the existing Portuguese settlers who stood in as godfathers, then gave the new converts their own name. That Goan Catholics bear Portuguese names is to be explained by this method of conversion, and not by their birth. As with the rest of India and indeed the world, there has been considerable miscegenation but it is ignorance and prejudice that still leads to descriptions of Goans, and of Goan Catholics in particular, as a mixed race.

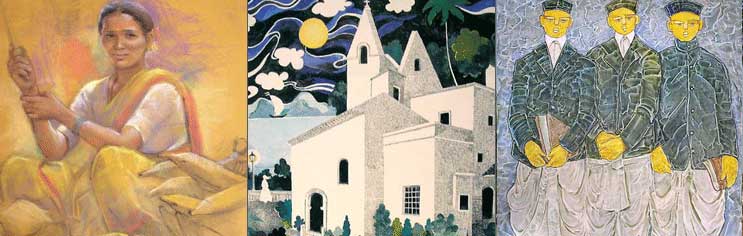

Souza's work, in so far as it deals with Goa, is rooted in landscape, religion and a rural way of life. Buffaloes cool themselves in ponds that shimmer in the noonday sun; "Landscape with train" (1944) evokes the gasps of one's childhood as the train chugged past the awesome and breathtaking beauty of cataracts, weaving its way in and out of a succession of tunnels that cut through the Western Ghats, the sheer drop visible as one emerged into the light, the smell of vegetation and dense foliage glistening after sheets of monsoon rain and the train finally, having left British India behind, speeding towards its destination — the beckoning palms, verdant paddy fields, clear waterways and graceful villages of Goa. He illustrates women lazing on verandahs, the dusky beauty of tribal women, their glossy hair encircled in wreaths of fragrant jasmine and abolim flowers, families seated on the balcony or front porch from which vantage point, news as gossip is generated and disseminated with passers by and neighbours. The day is punctuated with mealtimes at home and the lunch break for the labourer in the field with canji, a watery rice which is eaten with pickles, green mango preserved in spiced brine or salted fish served in typical utensils. "Goan Peasants in the Market" (1944) brings to mind the most famous market in Goa, the Mapuca market, which is set up every Friday. It is a hive to which people from distant corners throng for their provisions — poultry, the best produce from field and grove, fresh fish and masses of the preserved stuff, every conceivable item a household may need. There is gossip, friendship, coquetry and wily bargain amid the whiff of condiments and pickles. The palm trees visible make the scene distinctively Goan.

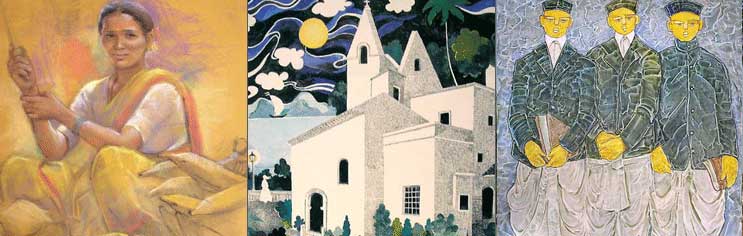

Souza's brush captures the community at work, at rest and at prayer. "Church in Goa" (1948) is a typical Sunday morning scene, a trail of villagers walking up the hill, men in white linen suits, panama hats and a walking stick which was the attire of the batcar or landlord. The procession leads up to the church, the vicar and the music school. He illustrates the pillars that hold up the tiled roof along the airy and spacious verandah where village children congregate. The church still remains an important centre for social intercourse: marriages planned, alliances effected, prospective partners glimpsed, disputes settled.

The women on his canvas pray, work and mourn. The mourning period in Goa is very strictly observed and the regulation black still prevails for months and years depending on the relationship to the deceased. Most moving and evocative is the traditional dress in which he represents his women, seen very clearly in "Priest with Goan women" (1944). This costume, known as vol in Konkani and lengol in Portuguese, which literally means a sheet, consisted of two sheet-like pieces of cloth worn over the sari or over yet another traditional and richly ornamented costume known as the bazu torop or pano baju. One sheet was draped around the hips to cover the lower part of the body till the ankles and the other tucked around the waist and then hoisted up from the back to veil the head so that only the face appeared and gave these widows and mothers (single women did not wear this attire) a nun-like appearance. Occupying the front section of the church, bowed in prayer, these rows of white clad devotees embodying a community truly at worship, was a familiar sight during Souza's childhood. The painting illustrates an epoch in Goan cultural history. This form of dress was abandoned by the upwardly mobile for the western dress and more recently for the sari. Souza's Goans are people of the soil: "I painted the earth and its tillers with broad strokes. Peasants in different moods, eating and drinking, toiling in the fields, bathing in a river or lagoon, climbing palm trees, distilling liquor, assembling in church, praying or in procession with priests and acolytes, carrying the monstrance, relics and images; ailing and dying, mourning or merrymaking in market places and feasting at weddings."

Music as a form of prayer and as accompanying every ceremonial and informal activity was intrinsic to the village home into which Souza was born, which is why his early work encodes religious symbolism revealing a seminal presence in his consciousness. Goa, it is often said, is haunted by the cross; little white crosses dotting the countryside. Candles flickering in the distance, steeples shimmering in the morning sun. The region is divided into villages that are predominantly Catholic or Hindu and Saligao is a predominantly Catholic village with a considerable Hindu population, and a church, the Mce de Deus, one of the most beautiful in Bardez.

The first 12 years of an artist's life are perhaps the seedbed of his creative life. In the case of Souza, this influence may be summarised as being rural Catholic life as experienced in daily companionship with his grandmother. Her influence with the vitality of folklore gave him a sense of the animistic and spirit ridden atmosphere of fields and home. The ritual symbols of Cross, monstrance, ciborium, on a platform that resembles the Judaic Ark of The Covenant, but with surfaces which are distinctly Goan, are frequently found in Souza's paintings and represent the passion and dread of a heretic creed seeking legitimacy and acceptance.

Colour, sound and drama which accompanied the Christianisation of Goa informs Goan social, cultural and religious life. Since Indian tradition is equally rich in spectacle, music and a form of worship which merges the meditative with a joyous spirit of abandon, Souza no doubt absorbed from birth, the joy, fanfare, grandeur and awe of processions of priests followed by lay Brotherhoods in capes of various colours, women and children dressed as vestal virgins and angels, accompanied by an enthusiastic band of musicians made up of farmers, carpenters, tailors, teachers. They take place with clockwork regularity all the year round.

The Crucifixion, the Deposition, the Supper at Emmaus which is symbolic of the leap of faith, the Pieta, each a representation of Christ's agony on the Cross are the recurring themes of Souza's work, seared as they must be into the artist's very being. Even insects, enormous dark figures lurking amid the rafters and high ceilings of ancient Cathedrals, stare transfixed out of his canvas. They were perhaps seen by the child as they circled and swooped when disturbed by the ringing of bells, the resounding chords of organ music or by the congregation belting out hymns. Vampirish, yet human, they communicate pain, predatory in their rage. The Passion of Christ must have come alive in a childhood which witnessed dramatisations of the Agony called the Santos Passos, which literally means Holy Steps in elaborate processions through the streets with life-sized statues held aloft. Their expressions of inexhaustible suffering, pierced and bloodied, could not have but communicated fearsome fantasies to an imaginative child. During Lent the vibrant world of colour disappears, the child wakes to 40 days of denial, watches adults mortifying themselves with fasts, the Church and the altars at home in deep purple and black that shroud ornament and statuary; women in black, children in spotless white; music a lament.

A LONELY child, surrounded by the reality of prayer as a way of life, he was pulled into primal intimations through his grandmother's stories of tortured saints and her daily activities, not least the prayers and cures for childhood ailments attributed to the evil eye. Indeed, like most rural societies, Goa is rich in indigenous cures made up of medicinal plants, onion juice, country liquor, hot poultice and cold compress soaked in reeking concoctions and considered a magical cure — all from birth to death.

The patient often suffers much pain as for instance the practice of branding the limb for recovery from jaundice. Such medication was always accompanied by prayers, the burning of candles and incense, and it is quite likely that the artist, who contracted smallpox as child, was himself subjected to such an experience. His mother's vow that he would join the priesthood should he be cured appears to have created a deadweight of responsibility on a child's consciousness. A dream world was born: phantasmagoria, hallucinations, angels in paradise, the sun, moon and stars personified, vividly imagined. Souza's work communicates a fear and hatred of the practice and symbols of a religion that fascinate and revolt him in turn. He turns them over again as if playing with the conjurer's tools in a vain attempt to comprehend or destroy. He returns obsessively to make his Christ symbolic of suffering and mankind, dehumanised, vile and ugly, pitiable, surrounded by implacable fate and with no trace of the essence of Christianity the compassion and love that illuminates, for instance, the work of Roualt.

Souza flagellates both himself and those he has loved and by whom he has been supported, not least the Goan women in this life. Goan women, as women the world over, are often called upon to take the major responsibility as breadwinner. It could be caused by an errant husband lost to alcoholism, not unfamiliar given the fact that Goan liquor, distilled from coconut palm and from the cashew fruit, and called feni, is both potent and cheap. Accounts of migrants in the community led to a keen awareness of the world beyond, of frontiers of opportunity. Small wonder then that when two months after his birth Souza's father died, his mother fled to Bombay leaving him in the care of his grandmother for some time, and made a living as a dressmaker and milliner. His grandmother's influence and environment shaped his consciousness of roots, his mother, and his wife Maria, were the power that gave him financial and psychological sustenance in the early ears.

They believed in him, sacrificed a great deal of themselves for him. Maria supported him in London working as a couturier, sought after by prestigious fashion houses. She made great headway for herself and her then unknown husband when Vogue featured, through her intervention, a piece on the artist and a design created by her. Later, she ran October Gallery, which was unique and innovative in what it sought to display. Yet, one is conscious of the singular absence of any acknowledgement of these women of faith and courage.

Belatedly, in a letter to Maria dated May 14, 1984, he writes: "I have always appreciated the way you have rooted for my art, you were involved in it almost from the time I was out of Art School and had started out on my own."

FOR one capable of such expressive prose, his reticence about his family is intriguing and seems to suggest a paradoxical relationship with a milieu he detests, yet in which he finds the impetus for some of his best work. Souza's anguish on this score is palpable: "What was I originally? I was a blooming maggot on a dung heap. My childhood has been insipid: like an undigested bit of straw." The pastoral environment of his childhood is recollected in tranquillity: "The sight of flowers, the song of the bird, and rustle of rice, the smell of mangoes. In the mornings, I swam in a lake across the fields, luminous and flat, of an unbelievable blue descended as it were from the blues. Sails of small fishing boats gleamed white. Light on water, sound, movement, ripple, glitter. Kingfishers, mynas, parrots, bluebirds sat on submerged water-buffaloes. The edge of the lake ornamented with rushes, water lilies, lotus, coral, barnacle, and its great deep auriferous glittering bed was a playground for God's incarnations or Fisher Kings! "The glow of this experience is tarnished by exposure to Bombay with its rattling trams, omnibuses, hacks, railways, its forest of telegraph poles and tangle of telephone wires, its haggling coolies, its dirty restaurants, blustering officials and stupid policemen, lepers and beggars, its Hindu colony and Muslim colony and Parsi colony, its bug ridden Goan residential clubs, its reeking mutilating and fatal hospitals, its machines, rackets, babbits, pinions, cogs, pile drivers, dwangs, farads and din! The idyllic world of a Goan childhood is forever lost in a conflation of the dread world of Christianity, urban squalor and the dehumanisation of his fellowmen. Souza moved to Bombay after the age of five, keeping in touch with his grandmother's world during long summer vacations and recovering this experience later in adult life. In Bombay, which he calls a polyglot city, the Goan world is eclectic, informed by an urban Christianity that mingles with a mainstream culture while trying to preserve its identity. The city has, for instance, a unique institution called coor/khud,which in Konkani means literally a room. These are clubs run by village organisations situated in Dhobi Talao, Mazagaon, Byculla and Charni Road, which function as lodges available cheaply for those who live on small budgets, particularly, the sea faring Goan. Feasts of the village patron saint are celebrated, the rosary said every evening and funeral rites arranged and paid for when necessary. The tired city worker finds here the bonhomie and community life left behind which gives him a feeling of belonging despite the squalid reality. There are also institutions like the Catholic Gymkhana where the middle classes socialise in a bourgeois ambience, which Souza derides: the echoes of a European existence which had many of the pretensions of Europe, but few of its amenities.

His most recent work reveals the vibrant palette of a questing, if controversial spirit, engaged with political, religious and social issues including a series on religious hypocrisy. His exhibitions sponsored by Saffronart and Apparao Galleries mark a return to the stark, basic and elemental forms of line and colour shorn of all isms. Scenes such as "Church with Pilgrims" replace the earthy, strident affirmation of primordial Goa with a gentler and softer glow of childhood innocence and faith in simple and basic forms of line, colour and statement. A period of all passion spent. Rather than argue that Souza rages against the contradictions in his upbringing, I would like to suggest that therein lies his greatest strength. Souza's intellectual and artistic life evolved within an urban ethos which also embraced Europe through an English educational system, and metropolitan culture sustained by interaction with Britain.

THE talent nurtured from an Indo-European cultural influence already experienced in childhood was deepened and focussed by political consciousness and an awareness of existence through which he attempts a synthesis with codes in which his personal history merges with universal concerns.

hus the critic who wrote that "The Red Road" (1962) could have been painted anywhere in the world since it has nothing specially Indian about it, is doubtless unaware of the cultural meanings implicit in Souza's work. The red earth of Goa is the theme of many a poem, folk song and pious incantation. Red mud paths dissect the vibrant green of paddy fields, the dense foliage of coconut, jackfruit, cashew, areca nut and bamboo plantations. Embedded is also a code for Souza's eroticism: Tambre matti, the red earth, is the name given to the red light district in Panjim, Goa's capital city. Souza's originality rests on his restless attempt to wrestle with a vision, which could portray a sense of the sacred through the profane, odious, degrading reality of experience.

The mystery of a religion profoundly felt and feared when it intruded into the idyllic world of beauty and innocence seems to have failed him in its promise of redemption. A man possessed by religious symbols, he portrays the vessels of the redemptive sacrifice of the Mass in an endless succession of still-lifes, which do communicate the tranquillity he seeks. The Latinism of Roman Catholicism which the Portuguese introduced with fire, hell and brimstone, the flagellations, are combined with a sort of rhythmic dance which only a combination of deep rooted tradition can bring. This is evident in his paintings of processions of the Holy Week which have the pageantry of a Hindu festival, a Carnival atmosphere, and the figures of Christ, Souza as Sebastian, and the tools of the sacerdotal trade: the artist has indeed made of his art a sacred rite, surrendering himself and his talent to a ceaseless search for being. In this attempt, he reaches out to symbols as used in the earliest form of Christianity.

In conclusion, it may be said that Souza's despair and fury has contributed to the sharpness of line, the clarity of vision that led him to seek meaning in Indian Christianity in its most pristine form, not a spirituality that accompanied worldly power but the good news as heard by a society already deeply implicated in worship. Souza rages against his fractured self but finds repose in a combination of the Sebastian of Latin Christianity, the sanyasi, and himself, the Hindu artisan playing the Christian game to his own tortured image and likeness. |