|

Source: Livemint

Patron Jehangir Nicholson’s private art collection will finally be accessible to the public

In her office in the newly designed annexe of what was formerly known as the Prince of Wales Museum of Western India, curator Zasha Colah has a tiny blueprint of a museum. The design was commissioned by art collector Jehangir Nicholson to house his growing collection of Indian modern and contemporary art.

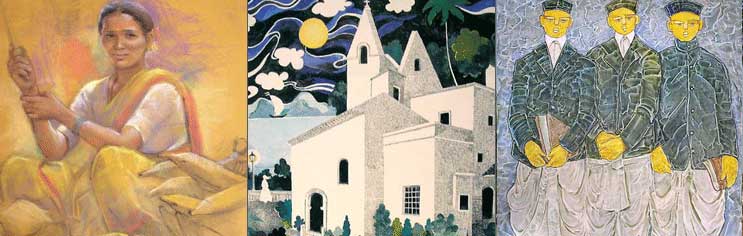

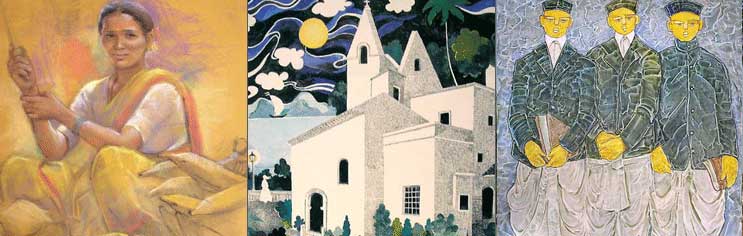

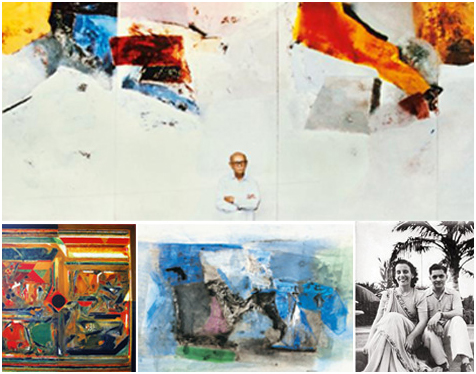

Canvas of life:(clockwise from top) Nicholson in front of a Laxman Shreshtha painting; Nicholson with his wife Dina ;artworks by Shreshtha and Raza (not from JNAF).Courtesy Jehangir Nicholson Art Foundation and CSMVS

A successful cotton merchant in Mumbai in the 1960s, Nicholson is said to have made routine trips around the city, architects in tow, to scout for possible locations to build a public museum. When he died in 2001, aged 86, his dream remained a blueprint.

On Monday, Nicholson’s entire collection of close to 800 paintings, sculptures, drawings and prints—from 1930 to 2001—will open to the public at the Jehangir Nicholson Gallery at the Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya (CSMVS, formerly the Prince of Wales Museum), where it will be on a long-term loan.

This is, possibly, the best fate for Nicholson’s formidable art collection; and for the man who spent half a lifetime trying to build his dream museum. A tenacious man, he’d even requested the Maharashtra government to provide him with 3,000 sq. yards in south Mumbai for the proposed structure, with no success.

But even in death he persisted. In his will, Nicholson directed the liquidation of all his assets to support a foundation that would manage his art collection, appointing his nephew Cyrus Guzder and his lawyer Kaiwan Kalyaniwalla as trustees. In a fortuitous move, and with the support of CSMVS director Sabyasachi Mukherjee, the two men managed to convince the museum board to accommodate the “Jehangir Nicholson Art Foundation” (JNAF) in its historic auspices. It is a coup for both parties: Nicholson’s legacy finds a home in prestigious real estate while his collection updates the museum’s collection of ancient Indian art.

A large part of CSMVS’ newly built second floor annexe is taken up by JNAF. When we visited early last year, in a room next to a sophisticated visible storage system where the collection is mounted on movable slides, Colah and her team were already preparing for the foundation’s inaugural show.

The Jehangir Nicholson Gallery opens with an exhibition titled Six Decades: Celebrating the Bombay Artists from the Jehangir Nicholson Collection and will run a curated programme of changing exhibitions thrice a year. The foundation also houses a research centre with an archive of letters, books and a workspace for long-term projects. Nicholson’s own photographs— an abiding passion since he was 12—are an important part of this archive.

What will pique the keen observer is that many of his photographs are of museums: of their architecture, display and lighting. Two months before he died, Nicholson had travelled to Spain to see the newly opened Guggenheim Museum Bilbao designed by the Canadian-American architect Frank Gehry. At 86, Nicholson was still making notes for his dream museum.

According to Geetha Mehra, director of Mumbai’s Sakshi Gallery, it was this trip that weakened him, and eventually led to his death.

Priming the palette

Nicholson’s own portraits show a determined spirit. He was a slight man, no more than 5ft tall. Born to a wealthy Parsi family, he was the director of his family’s cotton selection and purchasing agency Bruel and Co., established in 1863. Among his various maverick roles was that of the sheriff of Bombay, a post he held for one year.

He bought his first painting in 1968, a year after he lost his wife of 27 years. And his relationship with art filled a personal lacuna which was apparent in the way he addressed his artworks, often using terms of romantic love. That first canvas was bought from the Taj Art Gallery for Rs. 500: A Scenery by Sharad Waykool.

Nicholson started frequenting the Pundole and Chemould art galleries soon after. It was during this time that Kali Pundole, the founder of Pundole, introduced him to 24-year-old Laxman Shreshtha, who had just returned from art school in Paris.

Over the phone from Mumbai, Shreshtha recalls the beginnings of a tender friendship. He called him “Jangoo”, like all his friends. Nicholson would call him ritualistically at 8am to debate matters of art. “His curiosity to ‘get’ what art was about consumed him,” Shreshtha says.

Shreshtha introduced Nicholson to several other artists—Tyeb Mehta, Akbar Padamsee, S.H. Raza and M.F. Husain. On Shreshtha’s advice, he made studio visits and developed close friendships with many artists, most notably with Krishen Khanna. Nicholson’s understanding of contemporary art was formed from his conversations (and arguments) with those who made it, and other pioneers, gallery owners such as Kekoo Gandhy of Chemould. “He told me not to tell young artists that he was a collector. He wanted to talk to them on an equal footing,” says Gandhy, now 91.

Nicholson travelled across the country to pick up art. He bought 25 of Shreshtha’s works—the most of any one painter in his repertoire.

While his collection is deemed strongest in its wealth of modern masterpieces, he bought the works of contemporary painters such as Baiju Parthan, Jitish Kallat and Sudarshan Shetty as well. An important indicator of the value of this collection is that two of F.N. Souza’s most significant works ever—according to a list of five drawn by modern art expert Yashodhara Dalmia—belonged to him: Death of the Pope (1962) and Mammon(1961).

As a collector, he got progressively more methodological about what he bought. As he became increasingly conscious that he was collecting for a museum, his collection grew archival. According to Colah’s research, in 1996 Nicholson had about 150 paintings. In 1998, about 300. By 2001, he had collected around 800 works of art. He not only wanted one work from every important artist (the collection has 250 artists in all), he also wanted art that defined each artist’s distinct periods.

Raza’s shifting phases, for instance, are most dramatically characterized in the collection. Nicholson bought Razas through the 1940s, 1950s, 1960s, 1970s, 1980s, 1990s and in 2000.

Nicholson’s restless rearrangement and reordering of his collection—he would change the position of a painting in the middle of the night—reveals an obsessive streak. Kartik Mahyavanshi, who stayed with Nicholson in the last decade of his life, says he would be woken up at odd hours to move around canvases. These exercises have made Mahyavanshi such a warehouse of information that he has been hired as the foundation’s collection supervisor.

Evidently, Nicholson started to believe in the idea of a public museum early on. In 1976, he even loaned a part of his collection to the National Centre for the Performing Arts (NCPA) in Mumbai, but few knew of its existence. He called it the Jehangir Nicholson Gallery of Modern Art and donated substantially to have the space extended to house his entire collection, which did not happen. This preceded the opening of the National Gallery of Modern Art in Mumbai by 20 years, so it was the first public museum of modern and contemporary art in the city. Colah says contemporary artists such as Atul Dodiya recall spending their student days in its precincts because back then it was the “only place to see modern art”. This early donation is indicative of the rare merit of Nicholson’s patronage.

With the NCPA having agreed to restore the works in its possession to the foundation, the JNAF now boasts of Nicholson’s entire collection.

In a 1999 interview with The Indian Express, Nicholson had said his greatest concern was what would become of the art he had collected, after him: “Such a magnificent collection cannot be an inheritance to be enjoyed by just a few people.”

When the foundation opens its doors on Monday, a dream will come full circle, albeit posthumously.

The Jehangir Nicholson Gallery will open on Monday with Six Decades: Celebrating the Bombay Artists from the Jehangir Nicholson Collection, which will run till 28 August.

anindita.g@livemint.com

|