| |

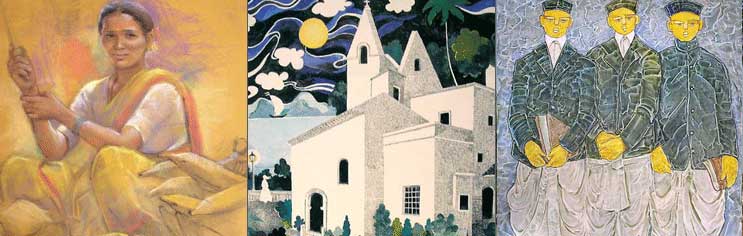

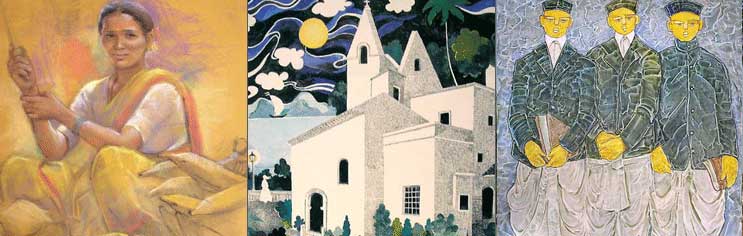

Aparanta, a major group show curated by eminent writer and art historian Ranjit Hoskote at GMC Complex, Panjim, Goa, during April 11- 24, 2007 was a major art event where 268 works of 26 artists were on display. In his curatorial note, he discusses the major issues that the show addresses and redresses. Aparanta, a major group show curated by eminent writer and art historian Ranjit Hoskote at GMC Complex, Panjim, Goa, during April 11- 24, 2007 was a major art event where 268 works of 26 artists were on display. In his curatorial note, he discusses the major issues that the show addresses and redresses.

Horizon and Confluence

Every exhibition that aims to represent or indicate the contours of a dynamic regional culture is a conversation about histories, about choices and predicaments, about contexts. An exhibition such as ‘Aparanta’ intervenes in an existing context; at the same time, it gestures towards the new contexts that it can help frame around the art-works that form its content. As a curator, I have always found exhibitions to be most productive when they deal with the problems that beset an art-making ethos, not when they celebrate what are taken to be the triumphs of that ethos. A problem, attentively handled, can be more rewarding than a triumph, complacently assumed; and therefore it is to a critical engagement with tribulations and crises that I turn, in this textual account of this exhibition.

‘Aparanta’ sets out to address, and to some extent redress, two major problems that have vexed the course of contemporary art in Goa. The first has to do with the representation, or lack of it, of Goan art in the outside world. Goan art has long been an invisible river, one that has fed into the wider flow of Indian art but has not always been recognised as so doing. This, despite the presence of such master spirits of Goan origin – active throughout the colonial, postcolonial and globalisation periods – as A X Trindade, Angelo da Fonseca, F N Souza, V S Gaitonde and Laxman Pai. This, also, despite the presence on the contemporary Indian gallery circuit, of consummately accomplished artists like Antonio e Costa, Querozito De Souza, Theodore Mariano Mesquita and Viraj Naik. The glossy stereotype is a more effective blinder than the heated needle of the mediaeval executioner: the associations of sun, sand, sex and carnival with Goa are so pervasive that even the better informed denizens of the Indian art world seem unaware of the vibrancy of the art scene in Goa. Fragmentary, unorganised and factionally divided as it may appear to the casual observer, the Goan art scene finds its definition around a number of inspired individuals who defy the apathy of India and the defeatism of their peers; around groups of artists acting collegially towards a higher common purpose; and around the cluster of compelling psychic and historical contents that spur them on to artistic exploration. Contemporary art in Goa is a confluence of generations, positions and locations. The graphicist and the oil painter coexist, and a taste for video installation complements, rather than displacing, a preference for watercolour. A member of the Goan diaspora returns from long years in East Africa or North America to memorialise the landscapes of his homeland, while the celebrated international artist shifts base from the northern city of her birth to live and work in a Goan village, backing up this existential choice with a sensitive portraiture of her new neighbours.

The second problem that ‘Aparanta’ addresses has to do with the internal development of Goan art, the nature of its practice and the circumstances of its production. Any sensitive viewer who spends a few days in Goa, visiting studios and galleries (they are often the same space, since the absence of a well-anchored gallery practice obliges artists to be their own agents, entrepreneurially producing and distributing at the same time), will find that Goa has brilliant, meteorically brilliant artists. But the lack of a context has left them afloat in a void of discussion. Geographical contiguity does not mean that Goa and mainland India share the same universe of meaning: Goa’s special historic evolution, with its Lusitanian route to the Enlightenment and print modernity, its Iberian emphasis on a vibrant public sphere, its pride in its ancient internationalism avant la lettre, sets it at a tangent to the self-image of an India that has been formed with the experience of British colonialism as its basis. The relationship between Goa’s artists and mainland India has, not surprisingly, been ambiguous and erratic, even unstable.

This is not to downplay or erase the connections that artists from Goa have made with Mumbai, Baroda, Hyderabad,

Santiniketan and other centres of art-making in India; Goan artists have lived and worked elsewhere since the late 19th century and early 20th century, from A X Trindade through F N Souza to more recent figures. Nor is this to neglect the fact that, conversely, artists have come to Goa and studied or worked there, treating it as a base, a lifeworld and a source of inspiration. They have been drawn, at various points, by the atmosphere of mental freedom and social receptivity prevalent during the Flower Power era of the 1970s, or the elegant mix of relaxed anonymity and courtly regard with which a Goan village treats its distinguished émigré resident today. Goa’s art has always been a confluence of various energies.

Indeed, I would place the idea of the confluence at the core of our current project. And even if we have not been able, for a variety of practical reasons and unavoidable circumstances, to include all the artists we would have liked to represent here, a confluence of the various strands that form the contemporary art scene in Goa remains an active ideal for ‘Aparanta’. The title of this exhibition is derived from the Sanskrit word aparanta – which carries the sense of ‘that which lies just this side of the Beyond’, ‘that which is at the horizon’. It is the ancient name applied to the Konkan coast by the administrators of the Mauryan empire and describes Goa beautifully, conveying the spirit of a richly confluential society that have been nourished by diverse cultural sources, among them, Indian and Iberian, Kashmiri and Persian, Arab and Chinese, Mediterranean and East African, Hindu and Catholic, Sufi and Bhakti.

It is no coincidence that the exhibition unfolds in Panjim, which, symbolically of our project, stands at the confluence of two rivers and the sea. Supported by the Goa Tourism Development Corporation (GTDC) and held at the old Goa Medical College building, a heritage structure, ‘Aparanta’ is intended to make a major statement: that Goa, far from being a cultural backwater remote from the centres of Mumbai, Delhi and Bangalore, is a seed-bed of artistic excellence.

The Exhibition: Structure and Contexts

‘Aparanta’ has its genesis in an art camp at Farmagudi, held in early 2007 and sponsored by the GTDC. However, it has evolved well beyond the array of 38 works that emerged from the camp, with each of the 19 artists producing one canvas work and one work on paper. While considering these works as an assembly of images, it became clear that an abundance of largely untapped contemporary art awaits the viewer in Goa. Further, it became evident that this exhibition could be used as the occasion to emphasise the pivotal place that Goa enjoys in the circuit of Indian art: a number of artists of Goan origin, or inspired by and trained in Goa, have gone out into the larger Indian art context and made their mark. Simultaneously, major artists from elsewhere in India have either relocated to Goa or contribute to Goa’s cultural life.

‘Aparanta’ has thus grown far beyond the original parameters of the art camp. I envisage ‘Aparanta’ as an exhibition project built around four key intersecting axes: first, the work of Goan artists resident in Goa; second, the work of Goa-trained and Goa-inspired artists working elsewhere in India; third, the work of artists from elsewhere in India who live and work in Goa; and fourth, the work of legendary artists of Goan origin, who have contributed to postcolonial Indian art.

Curatorially, I visualise ‘Aparanta’ as a concert of soloists: with each artist being shown to advantage, while yet forming part of a larger and coherent presentation. ‘Aparanta’ showcases the work of 22 artists. We have the 19 artists who participated in the Farmagudi Camp: Antonio e Costa, Giraldo de Sousa, Alex Tavares, Subodh Kerkar, Viraj Naik, Siddharth Gosavi, Pradeep Naik, Yolanda de Sousa Kammermeier, Querozito De Souza, Wilson D’Souza, Rajendra Usapkar, Sonia Rodrigues Sabharwal, Nirupa Naik, Liesl Cotta De Souza, Shilpa Mayenkar/Naik, Chaitali Morajkar, Santosh Morajkar, Hanuman Kambli and Rajan Fulari.

We also have three highly regarded artists who were specially invited to participate in ‘Aparanta’: the photographer Dayanita Singh (New Delhi/ Saligao); the painter and intermedia artist Baiju Parthan (Bombay); and the digital-media artist and painter Vidya Kamat (Bombay). Every artist in the exhibition is represented by a substantial selection of works. In addition, I have attempted to signal the presence of some of the master spirits of Goa’s art through occasions in the flow of the exhibition design that I think of as ‘shrines’: spaces containing traces, representative paintings and notations, devoted to Angelo da Fonseca, F N Souza, V S Gaitonde and Laxman Pai. At the time of writing, with works coming in from studios, collections and galleries, ‘Aparanta’ boasts about 265 art-works, among them paintings, drawings, graphics, photographs, mixed-media composites, and a projection-based environment. All this has been achieved by a dedicated core team in exactly seven weeks from preliminary discussion to the opening of the exhibition. ‘Aparanta’ is unabashedly monumental in scope, scale and ambition; it has been mobilised despite serious odds of time and preparation. All the same, I see it, not as a final destination, but rather, as a pilot, a proposal, a draft for a sequence of future exhibitions.

Every enterprise, however ambitious it may be, comes into being against a historical backdrop. I would contextualise ‘Aparanta’ in terms of a history of endeavours that reaches back to the early 1970s. Space permits me to pick up only three of these key moments or conditions, in this essay; but these three are crucial to our understanding of the direction that art in Goa has taken.

First: the foundation of the Goa College of Art, with the Paris-trained Laxman Pai at its helm, in the early 1970s. With the birth of the GCA, Goan art had a centre of gravity for itself, charged with optimism and anticipation, even if it did not always realise its dreams in practical terms; here was a forum for growth to set alongside Santiniketan and Baroda, and which would ensure that students did not have to migrate to distant places to refine their talents.

Second: the establishment of the Goan Art Forum during the early 1990s. This platform was nourished by the fervour of young Goan artists and art historians who had studied in Baroda and were eager to convey the impulses of the wider world to their homeland: Omprakash, Apurva Kulkarni, John Rodrigues and Theodore Mesquita were among its prime movers. In its best years, the Goan Art Forum brought about a sense of purpose and camaraderie that has, despite later changes, played a major role in the careers of a number of contemporary Goan artists.

Third: I would locate the ‘Aparanta’ initiative as the most recent moment in that stream of interest in Goan art that has been shown by commentators, collectors and curators from outside Goa. In this connection, we must recall the role played by institutions such as the Fundacao Oriente; by individual diplomats, connoisseurs and gallerists who formed a personal and cultural attachment for Goa and its artists, a species of amatore of whom Rudolf Kammermeier is a representative today; and, in many ways most vitally, by Ebrahim Alkazi, pioneering organiser of postcolonial Indian art and friend of the Progressives, who was one of the earliest to recognise and consistently support young Goan artists through his Art Heritage Foundation and Gallery, New Delhi |